May 4, 2019

“Unarguably the best single-volume biography of Churchill . . . A brilliant feat of storytelling, monumental in scope, yet put together with tenderness for a man who had always believed that he would be Britain’s savior.” —Wall Street Journal

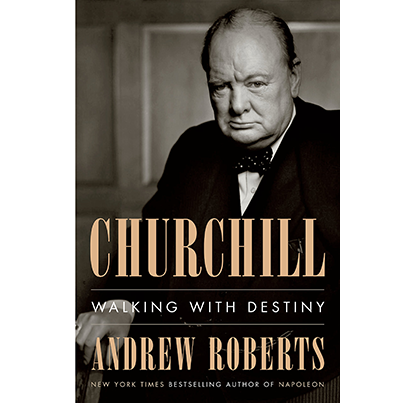

As part of the Museum's 50th Anniversary celebrations, Churchill Fellow Andrew Roberts presented an informative and engaging lecture on Churchill and humor, drawn from his his recently published and widely acclaimed Churchill biography, Churchill: Walking with Destiny, which is a New York Times bestseller. Roberts joins legendary Churchill biographer Sir Martin Gilbert to be the only person to twice give the prestigious Enid and R. Crosby Lecture.

MR. ROBERT MUEHLHAUSER: The Kemper Lectures have continuously attracted global experts in both British history, British- American history, and Winston Churchill for over the last 40 years.

For the last 20 or so, we’ve had the great pleasure of having these guest luminaries be introduced by someone who is well known for his great introductions. This man is a leading citizen in Kansas City and around the United States. Someone who needs no introduction.

Ladies and gentlemen, I give you Fellow Crosby Kemper.

MR. CROSBY KEMPER: So Fellow Muehlhauser, Marshal Jones, Mayor Cannell, Secretary Ashcroft, Senior Fellow Boeckman, fellow Fellows, members of the Churchill family, and ladies and gentlemen, thank you all for being here.

It’s a thrill to have Andrew Roberts back. It’s a thrill to be on this stage, which recreates the stage from which Winston Churchill gave the “Sinews of Peace”, the ‘Iron Curtain Speech.’

I assumed originally that we have moved from the church because I was going to tell some stories about Andrew that were inappropriate from the pulpit, but he’s told me that I cannot tell those stories. Though I think I will tell one, but in a moment.

Winston Churchill achieved fame in many ways but not least as a historian. His Nobel Prize for literature was certainly about his great triumphs in the writing of history. They’re still read by us, his History of the English- speaking Peoples, The Second World War. And our speaker has revised and extended the first with his own History of the English-speaking Peoples Since 1900 and provided a brilliant variation on the theme of the second with his Storm of War and Masters and Commanders.

Of course, it can’t be said of Andrew Roberts what Arthur Balfour said of Churchill’s history of the first world war, “The World Crisis,” that it was an autobiography discussed as a history of the universe. But Andrew’s histories and biographies share a relevance with Churchill’s in providing a guide to the presence and a sense of the character that is needed in our world to preserve the best for our future and for our children.

I must also say there’s no lack of Churchillian personal ambition in this. Andrew once said — boy, I hope, please, God, that he remembers he said this to me. Many years ago, at least 15 years ago, that he thought — or it was part of his ambition to be the prettiest historian.

Now, that has a wide array of connotations, I think. And his only rival he said could be Niall Ferguson. That may give you a sense of those connotations.

And I would say that it is certainly true today that we now know that the beauties of his Napoleon, his Churchill, his histories of the Second World War, and his continued achievements in the sartorial have firmly established his preeminence.

His genius, and I’m serious about that, is to use Churchill as historian and biographer to provide commentary, running commentary, on Churchill the man, Churchill the statesman, and in these unheroic times — Churchill the hero.

Alexis de Tocqueville in one of the most important if less remarked upon chapters of “Democracy in America” writes of the characteristics of historians in democratic ages.

The histories in aristocratic ages, he says, attribute occurrences to the will and temper of certain individuals, while the historians of a democratic age exhibit precisely the opposite characteristics. They are historians of great general causes of systems. What we would today call the sociology of history, the general reasons operating on the many and the multitude.

There is no question today that most historians would identify Churchill with the age of aristocracy, anachronistic, aristocratic, in need of revision.

It is one of the achievements of Andrew Roberts in this magnificent biography that his understanding of Churchill as a decedent of Marlborough, an admirer of Burke, the defender of traditions and of himself as the historian and soul of the British empire became — becomes a symbol for something much greater.

There are two words in Churchill: Walking with Destiny that recur again and again. The first is civilization, usually in the words of Churchill himself. Giving us what Tocqueville will call the special influences of individuals. Over and over again Churchill speaks of civilizations and in its defense.

The critique of everything that comes from the past, from our traditions that currently overloads our political and historical discussions is confronted by this Churchill endlessly defending what is good about our traditions and our civilization.

The second word used once or twice by Churchill himself in the biography but throughout the book by Andrew Roberts himself is paladin. Paladin.

Churchill is the paladin, the medieval knight errant of our modern world. The individual challenging the systems totalitarian military — sorry. Military, bureaucratic, sometimes quixotically, sometimes romantically, sometimes successfully, always nobly.

This is a biography of a hero, but it is not only an aristocratic hero but also a democratic hero with all contradictions but without irony.

Andrew Roberts first came to us as the biographer of Churchill’s rival Lord Halifax and was the author of a series of brilliant biographical essay “Eminent Churchillian” that were themselves the beginning of a revision of the revisionist historians.

And with this prize winning — and with his prize-winning biographer of Lord Salisbury, he has inaugurated — he has inaugurated a new era in which we may come to see this as the classic age of biography.

If in the words of Winston Churchill himself that the empire of the future is the empire of the mind, the great interpreter of the origins and foundations of that future in words like civilization and paladin will be our paladin of history.

Andrew Roberts.

MR. ANDREW ROBERTS: I’d like to preface my remarks today by saying what an honour and delight it is for me to speak on this historic hall and at this lectern, and to be only other person besides Sir Martin Gilbert to deliver the Crosby Kemper Lecture twice. Scientists are often said to be merely standing on the shoulders of giants, such as Sir Isaac Newton or Albert Einstein. Similarly, we Churchill biographers all stand on the shoulders of Sir Martin.

If Sir Winston Churchill had not been a statesman and author, he could have made a good living as a stand-up comedian. As early as 1947, before he had even become prime minster for the second time, ‘wit & wisdom’ books of his best jokes and quips were already being published. He had also become one of those lucky few to whom witticisms are attributed, whether they ever actually said them or not. A good deal of research has gone into finding out which witticisms Churchill did and did not say, principally by my friend Richard Langworth, and the result is that we now know that he has a body of well-attributed remarks that easily puts him on a par with his contemporary wits Oscar Wilde, Hilaire Belloc, Dorothy Parker, A.P. Herbert and Noel Coward, added to which he had the comic timing of Groucho Marx.

Wit mattered highly to Churchill, and he turned it into a very effective weapon in his political armoury — to charm audiences, of course, but also to deflect criticism, ridicule opponents, and sometimes to calm situations that were getting fraught. He well understood that he needed to entertain his audiences if he was also to instruct, persuade and — especially in wartime — to inspire.

His use of wit started early. When Mr Mayo, his Harrow schoolteacher, said to Churchill’s class, ‘I don’t know what to do with you boys,’ Churchill called out ‘Teach us, Sir!’ Asked in an interview in 1902 about the qualities desirable in a politician, Churchill said, ‘The ability to foretell what is going to happen tomorrow, next week, next month, and next year — and ... to explain why it didn’t happen.’ He could also quip of the job of an MP, ‘He is asked to stand, he wants to sit and is expected to lie.’

Many politicians of his time — indeed of our time too — would ponderously start their speeches with a set-piece joke to try to establish themselves as normal human beings, before getting down to the serious, political part of their addresses. By total contrast, Churchill would often pepper his serious remarks with witty asides throughout his speeches, forcing his audiences to concentrate all the harder as he lightened and darkened the tone at will.

A.P. Herbert, another great parliamentary wit of the day, pointed out that words on the printed page could not wholly do Churchill’s humour justice, ‘without some knowledge of the scene, the circumstances, the unique and vibrant voice, the pause, the chuckle, the mischievous and boyish twinkle on the face’. Even in the darkest days of World War Two, Churchill managed to inject humour into his speeches, indeed — as I will argue tonight — he did it especially during the darkest days of World War Two, knowing how good it was for the British people to know that their leader was not demoralized, but indeed was capable of making jokes however dire the situation got. Indeed, the darker the situation, the funnier his jokes became. This would have been impossible in anyone who did not believe that he was walking with destiny.

Churchill’s immediate predecessors as prime mininster — Andrew Bonar Law, Stanley Baldwin, Ramsay MacDonald, and Neville Chamberlain — rarely brought witty repartee into the Chamber of the House of Commons — some because they were simply incapable of it, others because they thought it unbecoming. By contrast, the expectation of a quotable witticism would fill up the Chamber as Churchill rose to speak. He used his wit to encourage high attendances both for his Commons orations and for his public speeches around the country. When he started out on his political career, in the days before radio, people who came to his speeches would know that they would be the first in the pub or back at home to repeat the jokes he had made.

Churchill honed his wit when he stood for parliament seven times in the eleven years between 1899 and 1910. Often by replying to hecklers on the election stump. Standing as a Liberal in his 1908 by-election, Churchill asked, ‘What would be the consequence if this seat were lost to Liberalism?’ Now, it’s always a risk to ask a rhetorical question to a lively audience, because during the pause that must follow the question for the portent to sink in, someone might shout out something funny that undermines it. Sure enough, on this occasion when Churchill asked ‘What would be the consequence if this seat were lost to Liberalism?’ a heckler shouted out ‘Beer!’, because the Tories were always promising to cut the price of ale. ‘That might be the cause,’ Churchill immediately replied, ‘I am talking of the consequence.’ Later on another heckler yelled ‘Rot!’ at one of his points. ‘When my friend in the gallery says “Rot”,’ Churchill riposted, ‘he is no doubt expressing very fully what he has in his mind.’

Such sallies were part of what people had come along for, and the word ‘laughter’ appeared more than forty times in The Times’ newspaper

report of the meeting. I can assure you that the word laughter hardly

ever appeared in the reports of speeches by Andrew Bonar Law or Neville Chamberlain, let alone forty times. ‘The Times is speechless,’ he also

joked during that by-election, ‘and takes three columns to express its speechlessness.’ Of the Liberal Party’s support for Irish Home Rule, he added, ‘and thousands of people who never under any circumstances voted Liberal before are saying that under no circumstances will they ever vote Liberal again.’

The art of the riposte was central to Churchill’s fame as a public speaker, and it meant that few wanted to take him on. He was once called a ‘dirty dog’ by the Labour MP Sir William Paling, and retorted ‘May I remind the Hon member what dogs, dirty or otherwise, do to palings?’ He enjoyed playing with the names of people, saying of an MP called Bossum that he was neither the one thing nor the other. When told that General Plastiras — which was pronounced Plaster Arse — had become Prime Minister of Greece, Churchill asked ‘But does he have feet of clay?’

The jokes were not always directed against people; when the man who was taking the photographs for Churchill’s 75th birthday said ‘I hope, sir, that I will shoot your picture on your hundredth birthday,’ Churchill replied, ‘I don’t see why not, young man. You look reasonably fit and healthy.’

Overall, of course, his witticisms were directed against political opponents, which of course also might go some way to explain why he was so unpopular in his Wilderness Years. ‘He spoke without a note,’ he said of a Labour MP in 1930, ‘and almost without a point.’ When a Tory MP left the Conservatives to stand as a Liberal, he described it as, ‘The only instance of a rat swimming toward a sinking ship’. Of the aristocratic MP George Wyndham he said, ‘I like the martial and commanding air with which the Right Honourable Gentleman treats facts. He stands no nonsense from them.’

What forcibly struck me again and again while researching and writing my biography of Churchill was how he constantly made jokes throughout the worst crises in modern British history, in 1940-41, when the Nazis were threatening to invade this country. There was no moment so bad that he couldn’t lighten the mood, and improve the morale of everyone around him, through the targeted deployment of humour. ‘When he was at No. 10 there was always laughter in the corridors,’ recalled his private secretary Jock Colville, ‘even in the darkest and most difficult times.’

Just after the Dunkirk evacuation, for example, when the head of the Royal Navy, Admiral Sir Dudley Pound, brought Churchill the long list of all the ships sunk and damaged in the operation, Churchill told him, ‘As far as I can see, we have only the Victoria & Albert left.’ The Victoria & Albert was the royal yacht. After the fall of Belgium, Holland, and Luxemburg, when Colville took him a telegram while he was dressing for dinner, Churchill said, ‘Another bloody country gone west, I’ll bet.’ Three days before Paris fell, when at the crisis meeting at Briaire the French Prime Minister, Paul Reynaud, asked Churchill what his defence plans were for the expected German invasion of Britain, Churchill replied, ‘I haven’t thought that out very carefully, but, broadly speaking, I should propose to drown as many as possible of them on the way over, and then knock on the head anyone who managed to crawl ashore.’ He said this in his excecrable French — ‘frappez sur le tête’ — and sadly history does not relate the French reaction to such levity at such a calamitous moment for Allied forces. To maintain a sense of humour at such a desperate moment showed how effortlessly Churchill could lighten tension when needed. Fortunately, he had left the conference before Weygand predicted to Reynaud that within a month, Britain would have ‘her neck wrung like a chicken.’

In the same speech on 4 June 1940 in which he said that in a thousand years men would still say that it was the British Empire and Commonwealth’s ‘Finest Hour’, Churchill made a joke about the Italian Navy, which had performed badly in World War One. ‘There is a general curiosity in the British Fleet to find out whether the Italians are up to the level they were in the last war,’ he said, ‘or whether they have fallen off at all.’ The writer Peter Fleming analyzed why that particular joke went down so well with Parliament and the public, writing, ‘If he had ended “or whether they are even worse”, he would have scored a hit ... By employing a subtler twist of denigration he gave to the passage that characteristic lilt of gaiety and evoked in his hearers the agreeable sensation of being made privy to a personal code of humour.’

This personal code of humour of course had a side that some decried as heartless. On 7 August 1942, Lieutenant General William Gott had been shot down and killed in a plane in the Western Desert. That evening, when Field Marshal Jan Smuts, the Prime Minister of South Africa, accused Churchill of not appealing enough to religious motives in politics, Churchill replied with mock indignation, ‘I’ve made more bishops than anyone since St Augustine!’ It might have seemed insensitive to make a joke on such a sad day, but, as he wrote years later, ‘Who in war will not have his laugh amid the skulls?’ If humour had been considered unacceptable whenever there had been a tragic death in that war, Churchill would made no jokes at all, and as one who had served in the trenches of the Great War — and on four campaigns prior to that — he knew that humour even in the worst times has always been an invaluable part of soldiers’ psychological armoury.

Very many of Churchill’s jokes were self-deprecating, as when — at another dangerous time for him, during a no-confidence motion in July 1942 — he was attacked over the serious shortcomings of the A22 tank. ‘As might be expected,’ he said, ‘it had many defects and teething troubles, and when these became apparent the tank was appropriately rechristened the “Churchill.”’ Here the key word that makes that joke work is the self- deprecating ‘appropriately’. He knew and admitted that he had his own defects and teething troubles, and as a result he won the sympathy and support of the House which a less credible defence of the tank in question would not have brought him. Churchill’s capacity for using humour to deflect criticism or change the subject was to serve him well in the war years and beyond.

The flight of Rudolf Hess to Scotland in May 1941 gave Churchill some opportunities for joking, even though it was a very serious moment in the war, indeed Hess landed on the same night that the chamber of the House of Commons had been destroyed in an air raid. He was amused when the Duke of Hamilton told him that the Deputy-Fuhrer had chosen to fly to his estate in Scotland because Hamilton was Lord Steward of His Majesty’s Household. He had taken it to be a real rather than an entirely honorific title, and therefore would be able to urge his peace message upon the King, who Hess had wrongly thought might be in favour of the idea. ‘I suppose he thinks that the Duke carves the chicken’, Churchill joked to his entourage, ‘and consults the King as to whether he likes breast or leg!’

The consequences were not so humorous, of course: Churchill did not want anyone in Britain, America, or Russia suspecting that he or his Government was interested in peace negotiations. At lunch, explaining the whole bizarre story to the King, Churchill joked that ‘He would be very angry if Beaverbrook or Anthony Eden suddenly left here and flew off to Germany without warning.’ He told the public the truth: that it had been the deranged act of a man close to a mental breakdown; and indeed Hess attempted to commit suicide the following month. After extensive debriefing in the Tower of London, Hess spent much of the rest of the war at a camp near Abergavenny in Wales.

‘On all sides one hears increasing criticism of Churchill,’ noted the Tory MP Henry Channon on June 6 1941. ‘He is undergoing a noticeable slump in popularity and many of his enemies, long silenced by his personal popularity, are once more vocal.’ Churchill was nonetheless able to make light of this in his next Cabinet meeting. ‘People criticize this Government,’ he said, ‘but its great strength — and I dare say it in this company — is that there’s no alternative! I don’t think it’s a bad Government. Come to think of it, it’s a very good one. I have complete confidence in it. In fact there has never been a government to which I have felt such sincere and whole- hearted loyalty!’ Coming from someone who had been noticeably disloyal to a succession of Governments, this declaration of loyalty to his own one amused his fellow Cabinet ministers.

For years Churchill had been making a joke of the amount of criticism aimed at him. In November 1914, for example, he told the House of Commons, ‘Criticism is always advantageous. I have derived continual benefit from criticisms at all periods of my life, and I do not remember any time when I was ever short of it.’

Churchill would not mind waiting for the perfect opportunity for a ripose. After one of the Budget debates in the 1920s, Lord Monsell congratulated him on a crushing retort and asked him how he did it. ‘Bobby, it’s patience,’ Churchill explained. ‘I’ve waited two years to get that one off.’ His mastery of what one could get away with saying in the Chamber and his sense of comic timing are evident when he told the Labour Party who were barracking him, ‘Of course it is perfectly possible for honourable Members to prevent my speaking, and of course I do not want to cast my pearls before — those who do not want them.’ The word ‘swine’ to describeone’s political opponents was of course banned under Erskine May, the parliamentary rulebook. On that occasion, Labour members laughedfor such a long time after that joke that when debate resumed they had forgotten why they were barracking him in the first place. In another ill-tempered debate, this time about the General Strike, in which he had edited the very anti-socialist Government newspaper called the British Gazette, Churchill again deflected criticism, as so often in his career, with a well-timed joke, telling the Labour benches, ‘Make your minds perfectly clear that if ever you let loose upon us again a General Strike, we will loose upon you another ... British Gazette.’ The impact of Churchill’s jokes lay in his superb sense of comic timing delivering the punch-line, which was an essential feature of his wit.

Budget debates were — indeed still are — typically very boring in British politics, being all about finance, but in a typically Churchillian way he turned them into spectacles, so much so that the galleries were packed during his Budgets, and even the Prince of Wales came to one, turning them into fashionable occasions in Society. In the Budget debate in April 1931, when some MPs on the other side of the House complimented him on his Chancellorship, he replied, ‘I suppose a favourable verdict is always to be valued, even if it comes from an unjust judge or a nobbled umpire.’ When he said in another debate, ‘We have all heard how Dr. Guillotin was executed by the instrument that he invented,’ and Sir Herbert Samuel shouted out, ‘He was not!’, Churchill replied, ‘Well, he ought to have been’.

There were certain topics during World War Two on which he taught his listeners to expect jokes, which included his own loquacity, his appalling French, and any mention of Benito Mussolini. He once said of Charles de Gaulle that, ‘Now that the General speaks English so well he understands my French perfectly.’ His description of General de Gaulle as being like ‘a llama surprised in her bath’ is principally funny, I think, because he made the llama female. ‘I, of course, am exceedingly pro-French,’ he once told his entourage ‘unfortunately the French are exceedingly pro-voking.’ When, on another occasion, his friend Brendan Bracken said that de Gaulle regarded himself as a reincarnation of St. Joan, Churchill growled, ‘Yes, but my bishops won’t burn him!’ Sadly, he did not say ‘The heaviest cross I have to bear is the cross of Lorraine,’ which was actually said by General Louis Spears, the British representative to the Free French.

From Wildean quips to English High Irony to ruthless ridicule, Churchill’s capacity to joke was a powerful weapon that he deployed regularly. He very rarely resorted to set-piece gags, much preferring to riff off any situation he found himself in, but an exception came during a period of heavy criticism after defeats in the Western Desert in late 1941, when he joked how, ‘There was a custom in Imperial China that anyone who wished to criticize the Government had the right to ... and, provided he followed that up by committing suicide, very great respect was paid to his words, and no ulterior motive was assigned. That seems to me to have been, from many points of view, a wise custom, but I certainly would be the last to suggest that it should be made retrospective.’

This was also the period when he made tis great statement on opinion polls: ‘Nothing is more dangerous in wartime than to live in the temperamental atmosphere of a Gallup Poll,’ he said, ‘always feeling one’s pulse and taking one’s temperature. I see that a speaker at the weekend said that this was a time when leaders should keep their ears to the ground. All I can say is that the British nation will find it very hard to look up to leaders who are detected in that somewhat ungainly posture.’ If you want the concept of leadership summed up in three sentences, you could do worse than to choose those.

Churchill deployed understatement to excellent effect, especially if his listeners were expecting something portentous. In February 1943 he read out General Harold Alexander’s splendid message that ‘His Majesty’s enemies, together with their impedimenta, have been completely eliminated from Egypt, Cyrenaica, Libya and Tripolitania. I now await your further instructions.’ Churchill then added, ‘Well, obviously, we shall have to think of something else.’ When Churchill’s valet, Frank Sawyers, accompanied him on a flight from Algiers to England in February 1943, he said to him, ‘You are sitting on your hot-water bottle. That isn’t at all a good idea.’ ‘Idea?’ replied the Prime Minister. ‘It isn’t an idea, it’s a coincidence.’ Later that year, on the way to Roosevelt’s residence at Hyde Park, Churchill and his daughter Mary visited the Niagara Falls, which he had last seen in 1900. ‘Do they look the same?’ asked a not particularly bright journalist, whereupon Churchill replied, ‘Well, the principle seems the same. The water still keeps falling over.’

Of course, Churchill’s detractors, unable to match him in wit, tried to use his sense of humour against him, implying that his joking meant that he was not a wholly serious politician. Many are the letters and diary entries that echo Neville Chamberlain’s complaint to Lord Halifax of August 1926, ‘His speeches are extraordinarily brilliant and men flock in to hear him as they would to a first class entertainment at a theatre. The best show in London they say, and there is the weak point. So far as I can judge they think of it as a show and they are not prepared at present to trust his character and still less his judgement.’ There was a political price that Churchill had to pay in having a sense of humour. Someone that funny, Chamberlain was implying, could not also have good judgment.

On D-Day over 160,000 men landed in Normandy in twenty-four hours, parachuted from planes and landing on the five invasion beaches codenamed Omaha and Utah (Americans), Sword and Gold (Britain) and Juno (Canadian). Although there were over eight thousand casualties that day, of whom around three thousand were killed, but this was at the lowest end of the spectrum of what had been feared. Yet for all these grim thoughts, Churchill never lost his sense of humour. When an MP asked him on June 8 — D plus two — to promise the House that he would ensure that the same mistakes were not made after victory in the Second World War that had been made after the First, the Prime Minister replied, ‘That is most fully in our minds. I am sure that the mistakes of that time will not be repeated. We shall probably make another set of mistakes.’

On the afternoon of 1 May 1945, the day after Hitler’ death, the Commons Chamber was full of MPs expecting the announcement of Victory in Europe. ‘I have no special statement to make about the war position in Europe,’ Churchill said, ‘except that it is definitely more satisfactory than it was this time five years ago.’

As well as understatement, English high irony was another favoured genre of Churchillian humour. On July 20, 1944, a small group of German generals tried to kill Hitler in his East Prussian headquarters, the Wolfsschanze. For this joke to work it helps to know that Hitler’s paternal grandmother had been Maria Schicklgruber, and Hitler’s father Alois had that name until he legally changed it. ‘When Herr Hitler escaped his bomb on July 20th, he described his survival as providential,’ Churchill joked to the Commons in September, ‘I think that from a purely military point of view we can all agree with him, for certainly it would be most unfortunate if the Allies were to be deprived, in the closing phases of the struggle, of that form of warlike genius by which Corporal Schicklgruber has so notably contributed to our victory.’ On 2 August of ‘Corporal Hitler’ he joked, ‘Even military idiots find it difficult not to see some faults in some of his actions. ... Altogether I think it is much better to let officers rise up in the proper way.’

The next month, asked to give the House a ‘categorical denunciation’ of the prime minister of the collaborationist Vichy regime Pierre Laval, Churchill replied, ‘I am afraid I have rather exhausted the possibilities of the English language.’

As well as Britain’s enemies, Churchill also ridiculed his own political opponents relentlessly. A favourite butt was Aneurin Bevan, the Labour MP for Ebbw Vale, who kept demanding Churchill’s resignation during the war and after it said that Tories were ‘lower than vermin’. On the issue of Britain finally recognising Red China diplomatically in July 1952, Churchill said, ‘If you recognize anyone it does not necessarily mean that you like him. We all, for instance, recognize the right honourable gentleman, the Member for Ebbw Vale.’

Churchill was particularly good at puncturing the pomposity of oleaginous MPs. When, during Prime Minister’s Questions, one Tory MP suggested that the House should toast, ‘Death to all Dictators and Long Life to all Liberators Among Whom the Prime Minister is the First’, Churchill phlegmatically replied, ‘It’s very early in the morning.’ When a famously longwinded MP called for a national day of prayer and asked, ‘Will the Prime Minister assure the House that, while we have quite properly attended to the physical needs of defence and of our other problems, we should not forget those spiritual resources which have inspired this country in the past and without which the noblest Civilization would decay?’ Churchill replied, ‘I hardly think that is my exclusive responsibility.’ When he used the Latin expression primus inter pares (first among equals), and Labour MPs shouted out ‘Translate!’, ‘Certainly I shall translate,’ Churchill replied, ‘for the benefit of any old Etonians present.’

In his first speech after losing the 1945 General Election, Churchill joked how, ‘A friend of mine, an officer, was in Zagreb when the results of the late General Election came in. An old lady said to him, “Poor Mr. Churchill! I suppose now he will be shot.” My friend was able to reassure her. He

said the sentence might be mitigated to one of the various forms of hard labour which are always open to His Majesty’s subjects.’ Returning to the opposition benches in 1945 for the first time in fourteen years gave Churchill endless opportunities to use humour to critcise the Government, which he used unsparingly. On occasion he came to his opponent Clement Attlee’s defence, however, as when Stalin accused Attlee of being a warmonger over the Korean War and rearmament. Churchill retorted that as Labour was intending to call him — Churchill — a warmonger in the next election, so, ‘Stalin has therefore been guilty, not only of an untruth, but of infringement of copyright.’

The time of this speech has come when — with a heavy heart — I must disappoint a large number of you by telling you some of the large number of vey good and funny jokes that Churchill did not say. Richard Langworth has trawled all the sources long and hard, and in a chapter entitled Red Herrings in his book Churchill in His Own Words, he lays out ten pages full of false attributions. Richard and all other Churchill scholars have not been able to find a moment when Churchill told Lady Astor, or anyone else, that if he were married to her and she poisoned his coffee, then he would drink it. Nor did he say that if you’re going through Hell, keep going. He never called Clement Attlee ‘a sheep in sheep’s clothing’, nor did he say ‘An empty car drew up and Clement Attlee got out.’ He never said that ‘Britain and America are two nations divided by a common language,’ or ‘I know of no case where a man added to his dignity by standing on it,’ or ‘A fanatic is someone who won’t change his mind, and won’t change the subject.’ It is a great shame that among the red herrings is Churchill’s supposed reply to the threat from Ribbentrop that the Germans would have the Italians on their side in a future war: ‘My dear Ambassador, it’s only fair. We had them last time.’

Yet for all this, there are several hundred equally funny remarks that he did make. Churchill’s intelligence and speed of response and perhaps above all his great memory for repartee stood him in excellent stead, as in this story: He enjoyed inviting visitors, even comparative strangers, to his country house, Chartwell in Kent. On one occasion he offered a Mormon a whisky and soda, who replied, ‘May I have water, Sir Winston? Lions drink it.’ ‘Asses drink it too,’ came the reply. Another Mormon present said, ‘Strong drink rageth and stingeth like a serpent.’ Churchill replied, ‘I have long been looking for a drink like that’. When his private secretary Anthony Montague Browne later congratulated him on those ripostes, he grinned and said, ‘None of it was original. They just fed me the music hall chance.’

As a drinker, smoker and carnivore, outliving teetotalers and vegetarians never failed to give Churchill huge satisfaction, for as he said, ‘I get my exercise as a pall-bearer to my many friends who exercised all their lives.’ He also took great satisfaction from owning his 37 racehorses, and by the time of his death he had won seventy races. A few years after a victory

at Hurst Park in the 1950s, when it was suggested that his best racehorse Colonist II be put out to stud, he replied, ‘And have it said that the Prime Minister of Great Britain is living off the immoral earnings of a horse?’

Some decried Churchill’s use of humour as flippant, others as a cynical weapon to win popularity and deflect legitimate criticism, but it also reflected his extraordinary coolness under pressure, as well as his refusal to be cast down and his belief in the necessity of maintaining morale. He was an epigrammatist to rival Samuel Johnson and Sidney Smith, but unlike them he was witty while also saving his country during a world war.

On Churchill’s death in January 1945 Clement Attlee said, ‘I recall the long days through the war—the long days and long nights—in which his spirit never failed; and how often he lightened our labours by that vivid humour, those wonderful remarks he would make which absolutely dissolved us all in laughter, however tired we were.’ Winston Churchill might have offered his country ‘nothing but blood, toil, tears and sweat’ — but they weren’t all tears of pain and loss. Sometimes — when they were least expected but also most needed — they were tears of laughter too.

MR. TIMOTHY RILEY: Well, thank you, Andrew. As you rightly noted, you are only the second historian or distinguished guest to give the Kemper lecture twice. I think you may be the first to give it thrice. Thank you. You are welcome back.

“Leave the past to history especially as I propose to write that history myself.”